The single hardest moment in my life was telling Landon “Daddy died.”

Today is Children’s Grief Awareness Day, an initiative of the Highmark Caring Place, which offers support for grieving children, adolescents and their families.

Landon, Bryce and I have been involved with The Caring Place since the summer. These group sessions put us among other families who are walking a similar path. After dinner and game time, kids are divided into age-specific rooms where the same volunteers each week shepherd them through age-appropriate and research-backed activities that will help them process grief. Landon has made a memory box, several artwork pieces, a feelings monster and more. Our group is also making a big memory quilt where each square is dedicated to our loved one; that will be complete in January.

Adults also have our breakout time. It’s so important to be around peers where we can share openly, honestly and without judgment. Parenting is hard. Solo parenting is harder. Add in grieving children and our own grief, and it feels impossible.

The Caring Place staff is up-to-date about the latest research about how kids process grief and how we as adults can help guide them through this journey. Grief in children is misunderstood and often dismissed or downplayed with refrains of, “Children are resilient. They’ll be fine!”

Children are resilient and I hope they will be fine, but “fine” does not come without a lot of work. And fine or not, this will forever alter their lives in ways I can’t even begin to comprehend as an adult.

What is Grief?

The grief journey is a lifelong one. Landon was 4 when Brian died; Bryce only 8 months. Landon is processing his grief in the best way he can, but as he ages and his brain matures, he’ll constantly re-process it on new, deeper levels as he understands more about death. Bryce, too, especially as he grapples with not remembering Brian. They’ll understand it more as they watch their peers with both parents and wonder why their dad had to die. They’ll feel it more acutely at milestones that Brian would’ve so enthusiastically celebrated. They’ll feel it should they choose to get married and have children of their own one day. They and we will feel it always.

A few other grief factoids:

- Grief is not linear in anyone and especially in kids. There will be ups and downs.

- Grief doesn’t go away; rather, we grow around it. There is no finish line. There is no end date. There is no “We’re all better now.”

- Kids have a limited grief span and can cycle in and out of grief very quickly. Just because they’re laughing while everyone else is crying doesn’t mean they’re not sad. Their bodies and brains have only so much capacity for big feelings at one time.

- Kids are processing grief against the backdrop of normal growth and development. So whereas adults are fully developed while they process grief, kids must navigate grief amid the normal complexities of growing up, making both processes significantly harder.

- It is a guarantee kids will ask you the absolute hardest questions at the most inconvenient times. (This isn’t scientifically backed, but I can tell you it is true.)

How to Help

Children who lost a parent while growing up report it takes more than six years to move forward, yet more than half report waning support from family and friends within the first three months after the loss. A 2019 study also suggests that the younger a child is when a parent dies, the bigger negative impact it has on their lives. Kids need lifelong support to add even a little bit of light into the abyss of their sorrow.

This is by no means an exhaustive list, but these are a few things that can help kids as they grieve. Some are from personal experience in the past nearly eight months and some are suggestions from books and other resources.

- Show up. Whether that is in person or virtually, whether it’s once a month, once a quarter or just on select days like birthdays, show up when you say you’re going to. Kids who have lost a parent also lose a huge sense of security and develop anxiety over losing others, even if they don’t verbalize it. It’s important to show up when you say you’re going to.

- Talk to them. Tell kids stories about their deceased parent (or other loved one). Show them pictures or videos. Listen to old voicemails together. Ask them about their favorite memories.

- Respect their boundaries. While talking, be mindful of a child’s limited grief span. If they say they’re done after only a couple minutes, it’s because they’re going into mental and emotional overload and they need to step away. Don’t force a conversation. They’ll be back when they’re ready.

- Spend time. If you’re able to spend time with them as part of “showing up,” great! Bereaved kids often lack one-on-one time, especially if there’s more than one child in the home. The remaining parent is probably overwhelmed and might not always be able to dedicate as much individualized attention in a time when a child needs it the most.

- Have fun. Tell jokes and silly stories over the phone or FaceTime. Go do a fun activity together. Never lose sight that a child deserves to have–and needs–a childhood. Help give them the childhood they need while honoring their grief and their loved ones.

Learn more

The Caring Place’s YouTube channel has a whole series of videos and activities today that also will be available on-demand. I’m especially excited about Patrice Karst’s talk, author of The Invisible String, which is one of the absolute best books about grief for kids. (Adults, too!)

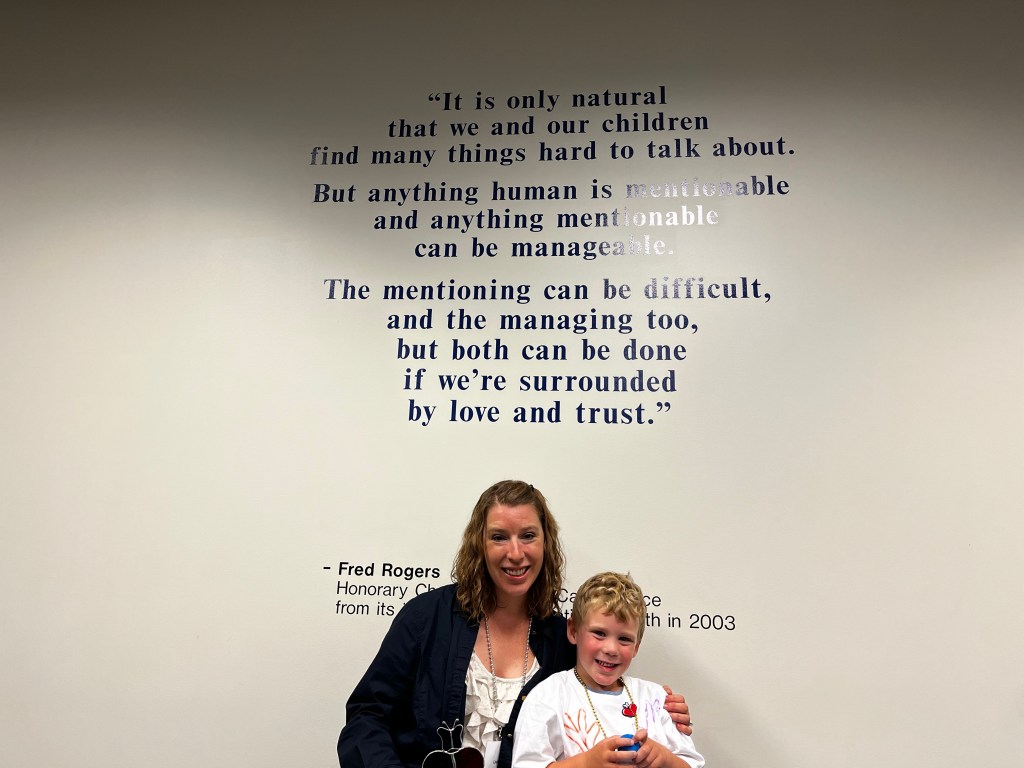

Fred Rogers was the honorary chairman of The Caring Place until his passing in 2003. The wall in the main gathering area has this quote painted on, which resonates so strongly and I just love:

“It is only natural that we and our children find many things hard to talk about.

But anything human is mentionable and anything mentionable can be manageable.

The mentioning can be difficult, and the managing too, but both can be done if we’re surrounded by love and trust.”

Fred Rogers

Grief is a terribly lonely place to be, but The Caring Place has made us realize we don’t need to do it alone.

Leave a reply to Bryan Reilly Cancel reply