One in 14 children will experience the death of a parent or sibling by the time they turn 18. Countless more experience other profound losses. Why is it, then, that we so rarely hear about a child’s grieving process?

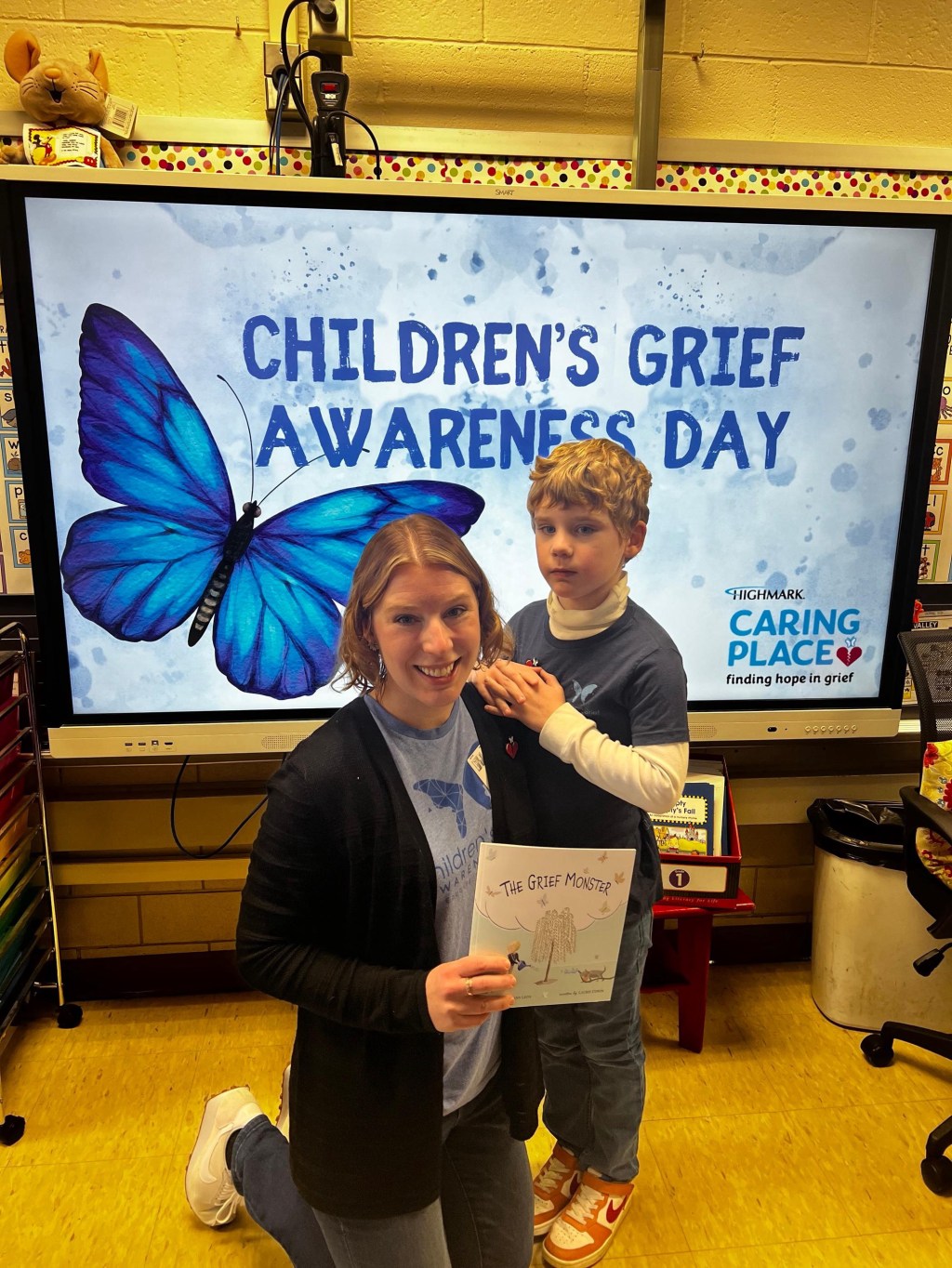

Nov. 20, 2025, is Children’s Grief Awareness Day, held annually the Thursday before Thanksgiving. The day acknowledges that a child’s grief is very real and aims to raise awareness as to how children grieve differently than adults and we can best step up to support them.

Before Brian died in March 2023, I had no idea such a day existed. To be honest, I’d never given a second thought to children grieving. Our sons were 4 years and 8 months, their grandparents were healthy and the idea of them experiencing a grieving event felt like a lifetime away.

We as a society sing refrains of “children are resilient,” “they’ll be fine,” “they’ll get over it” and “they’ll barely remember it.” Not only are these sentiments blatantly wrong; they are harmful. They are harmful to the children. They are harmful to the adults who care for them, love them and often are grieving alongside them.

A Challenge

This is our third Children’s Grief Awareness Day. The first year was about acknowledging it. The second year was about how we can support our youngest grievers. Now that this is our third year, I challenge everyone to go beyond knowing this day exists.

I challenge you to make the conscious effort to change your mindset about children’s grief and to consistently show up in meaningful ways. Don’t dismiss childrens’ grief as a fleeting emotion. Give it the acknowledgement and respect it deserves.

Resource: The Childhood Bereavement Estimation Model: In partnership with the New York Life Foundation, Judi’s House/JAG Institute developed the CBEM to understand the magnitude of the issue. The CBEM approximates rates of U.S. children and youth who will experience the death of a parent or sibling by the time they reach adulthood.

My early research about children’s grief revealed a startling statistic: Those who lost a parent said it took six or more years before they could move forward, yet 57 percent reported waning support from family and friends within the first three months following a loss.

Read that again. Let it sink in. More than half lose substantial support in the early days of grief. What do they do the remaining 5 years and 9 months before they can start to move forward? Who do they turn to? How does the surviving parent support their child and explain why people have disappeared?

We need to do better.

Grief is an uncomfortable emotion to sit with. It hurts to feel and it can be hard to witness. I think our reluctance to acknowledge it, accept that it’s real and witness it is all an effort to avoid the discomfort. But what we’re actually doing it perpetuating a cycle of grief intolerance. We try to avoid the emotion and in doing so often diminish our own and others’ grief. Accidental though it might be, we’re modeling grief intolerance to our children and the cycle continues through the generations.

Starting today, let’s break that cycle.

If You Don’t Know What To Say

That’s okay! I don’t know what to say to grieving people either. I know nothing I can say will make it better, and I also know that saying nothing and pretending like it doesn’t exist absolutely will make it worse.

Children feel deeply. They might not say it out loud for a couple reasons. I think some kids don’t want to say it loud and be perceived as different. They don’t want to stand out from their peers. They might be afraid of their grief being rejected or minimized. I’ve heard of some kids report being made fun of at school because a parent has died.

Children, especially younger ones, also may not know what words to put to these big emotions. They know they feel something big, but they can’t name it. Brian used to always brush Landon’s teeth. A few days after Brian died, Landon was fighting against toothbrushing while I was trying to brush his teeth. We were both frustrated. But amid the fog of my brain, I had a moment of clarity. “Landon,” I asked. “Are you upset that I’m brushing your teeth and Daddy isn’t?” “YES!” he yelled back.

I don’t think Landon had any idea what the root of his emotions were in that moment until he heard me say it out loud. Children need help naming their emotions and also knowing it’s okay to feel all of them.

“Children’s Grief Awareness Day allows us to advocate that any child old enough to love is old enough to mourn. We can all work together to be advocates and teach other adults how children are natural mourners but that they need the love and support of caring adults. To be “bereaved” in part means “to have special needs.” This day allows us to highlight what some of the special needs of grieving children are and help others create places where children experiencing grief are safe to openly and authentically mourn. And we know that if children mourn well, they go on to live well and love well.”

Dr. Alan D. Wolfelt, Founder and Director, Center for Loss and Life Transition

When a child shares they’re feeling sad or really missing something, you can always tell reply: “I don’t know what to say, but I want you to know I’m here for you. I hear you. This really, really stinks and it isn’t fair.”

Don’t minimize their grief. Don’t tell them to not be sad; it isn’t a switch someone to flip on and off. And do not be the “at least” person. (At least you had them for XX years. At least you have their memories. At least they’re in a better place.)

Ask them if they want to share a memory of their person, or ask them if they want you to share a memory of their person. They love talking about their person who died, both through sharing their stories and hearing new stories.

I want my boys to always remember Brian. The best way I can do that is by sharing photos and stories of him. This has helped Landon retain his too-few memories of his dad and although Bryce has no memories of his own, I hope sharing our memories will help Bryce feel like he knows him, too.

Show Up Meaningfully

How you can show up for a grieving child is quite simple: Just show up. That’s all. Literally just show up.

Show up how you wish people would show up for your child. Here are a few concrete examples:

- Very young children might just need someone to play with. Play is a critical part of child development. Help make sure they’re getting it.

- Older children might need someone to talk to other than their parent. Think especially: If a child’s father died, they’re going to need more male figures. If a child’s mother died, they’re going to need more female figures.

- Do activities with them. Special outings are always appreciated, but it doesn’t have to be that hard. Invite a child to join you while running errands or invite them on a hike or to a meal with your own family. Make them feel included. Show them the different forms family can take. Regularly include them as part of yours.

- Teach them. Teach them things their deceased person may have taught them. Teach them things you’re knowledgeable about and want to share.

Children aren’t looking for someone to replace their person who died; that’s not possible and it’s not what they want. On the contrary, I see children want to always remember their special person and share those memories with new people.

The Grief Monster

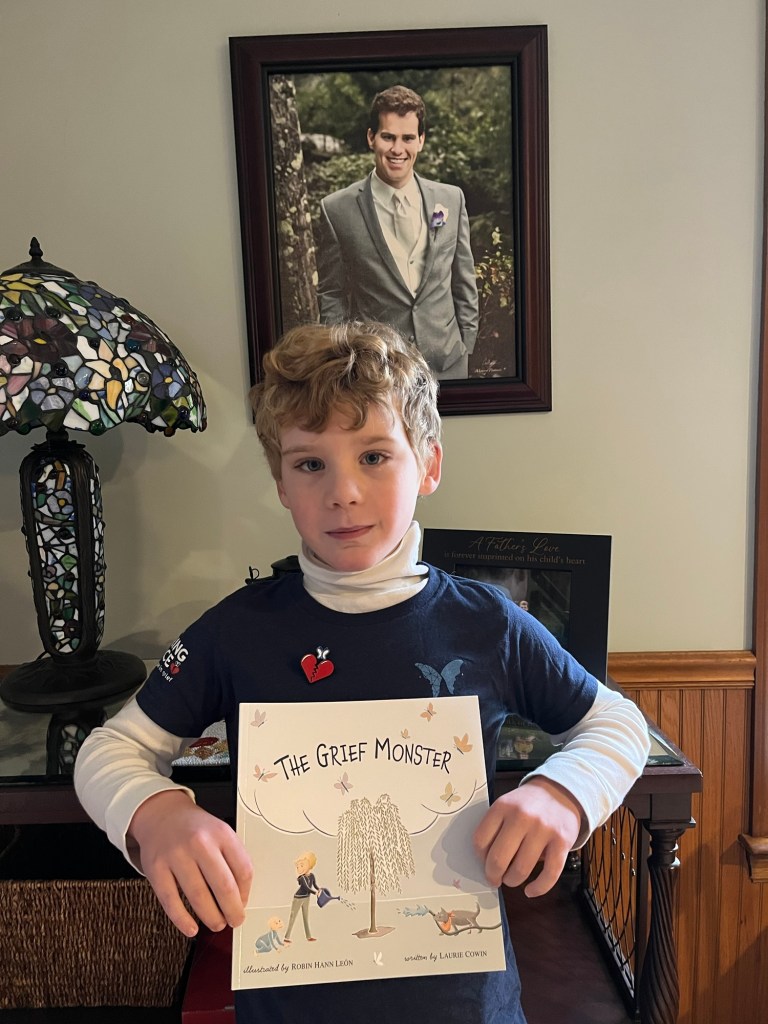

This Children’s Grief Awareness Day is extra meaningful because of my recently published children’s book, The Grief Monster.

I had the absolute honor of reading it to Landon’s class this afternoon, talking about emotions (and how they’re ALL okay) and making a butterfly craft with them.

If you haven’t already checked it out, I invite you to learn more about it. Available on Amazon, Barnes & Noble and Bookshop.org.

Children’s Grief Awareness Day is one day a year, but children need support and love every single day of the year. Let’s keep the conversations going and let’s keep on showing up.

Leave a comment